1. Logemann JA. The evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 1998.

2. Linden P, Siebens AA. Dysphagia: predicting laryngeal penetration. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1983;64(6):281-284.

3. Ward E, Morgan, AT. Dysphagia following traumatic brain injury in adults and children: Assessment and characteristics. In: Murdoch BE, DG. T, eds. Traumatic brain injury: associated speech, language, and swallowing disorders. San Diego: Singular Publishing Group; 2001:331-367.

4. Mackay LE, Morgan AS, Bernstein BA. Factors affecting oral feeding with severe traumatic brain injury. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation. 1999;14(5):435-447.

5. O'Neil-Pirozzi TM, Momose KJ, Mello J, et al. Feasibility of swallowing interventions for tracheostomized individuals with severely disordered consciousness following traumatic brain injury. Brain injury : [BI]. 2003;17(5):389-399.

6. Schurr MJ, Ebner KA, Maser AL, Sperling KB, Helgerson RB, Harms B. Formal swallowing evaluation and therapy after traumatic brain injury improves dysphagia outcomes. The Journal of trauma. 1999;46(5):817-821; discussion 821-813.

7. Lazarus C, Logemann JA. Swallowing disorders in closed head trauma patients. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1987;68(2):79-84.

8. Terre R, Mearin F. Evolution of tracheal aspiration in severe traumatic brain injury-related oropharyngeal dysphagia: 1-year longitudinal follow-up study. Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society. 2009;21(4):361-369.

9. Mackay LE, Morgan AS, Bernstein BA. Swallowing disorders in severe brain injury: risk factors affecting return to oral intake. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1999;80(4):365-371.

10. Cifu DX, Eapen BC, Janak J, Pugh M, Orman J. Traumatic Brain Injury Rehabilitation Medicine. Future Medicine; 2015.

11. Logemann JA. Evaluation and Treatment of Swallowing Problems. In: Zasler ND, Katz, D. I., Zafonte, R. D., ed. Brain Injury Medicine: Principles and Practice. 2 ed. New York: Demos Medical Publishing; 2013.

12. Horner J, Massey EW, Riski JE, Lathrop DL, Chase KN. Aspiration following stroke: clinical correlates and outcome. Neurology. 1988;38(9):1359-1362.

13. ONF-INESSS. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Rehabilitation of Adults with Modarate to Severe TBI. 2016.

14. Sørensen RT, Rasmussen RS, Overgaard K, Lerche A, Johansen AM, Lindhardt T. Dysphagia screening and intensified oral hygiene reduce pneumonia after stroke. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2013;45(3):139-146.

15. Hun Lee S, Shin Lee E, Ho Yoon C, Shin H, Lee C. Collet-Sicard Syndrome With Hypoglossal Nerve Schwannoma: A Case Report. Vol 412017.

16. Malik SN, Khan MSG, Ehsaan F. Effectiveness of swallow maneuvers, thermal stimulation and combination both in treatment of patients with dysphagia using functional outcome swallowing scale. 2017.

17. Jayasekeran V, Singh S, Tyrrell P, et al. Adjunctive functional pharyngeal electrical stimulation reverses swallowing disability after brain lesions. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(5):1737-1746.

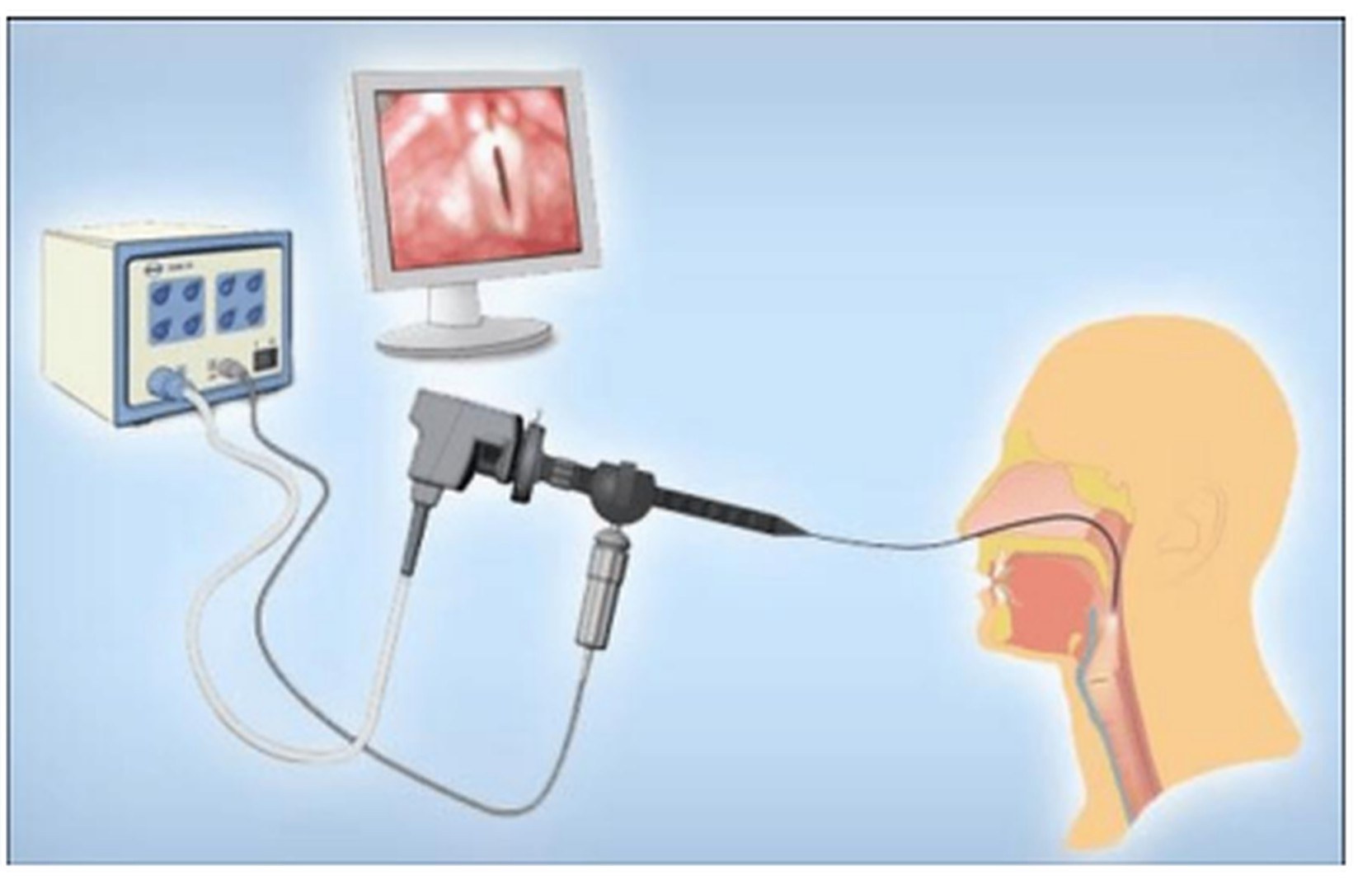

18. Sun SF, Hsu CW, Lin HS, et al. Combined Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation (NMES) with Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES) and Traditional Swallowing Rehabilitation in the Treatment of Stroke-Related Dysphagia. Dysphagia. 2013;28(4):557-566.